When you're managing type 2 diabetes, the goal isn't just lowering blood sugar-it's protecting your heart, kidneys, and overall life expectancy. That's where SGLT2 inhibitors come in. These medications, once seen as a backup option, are now front-line treatments for millions of people with diabetes who also have heart failure, kidney disease, or a high risk for both. But they’re not without trade-offs. Understanding the real benefits and real risks can help you decide if they’re right for you-or someone you care about.

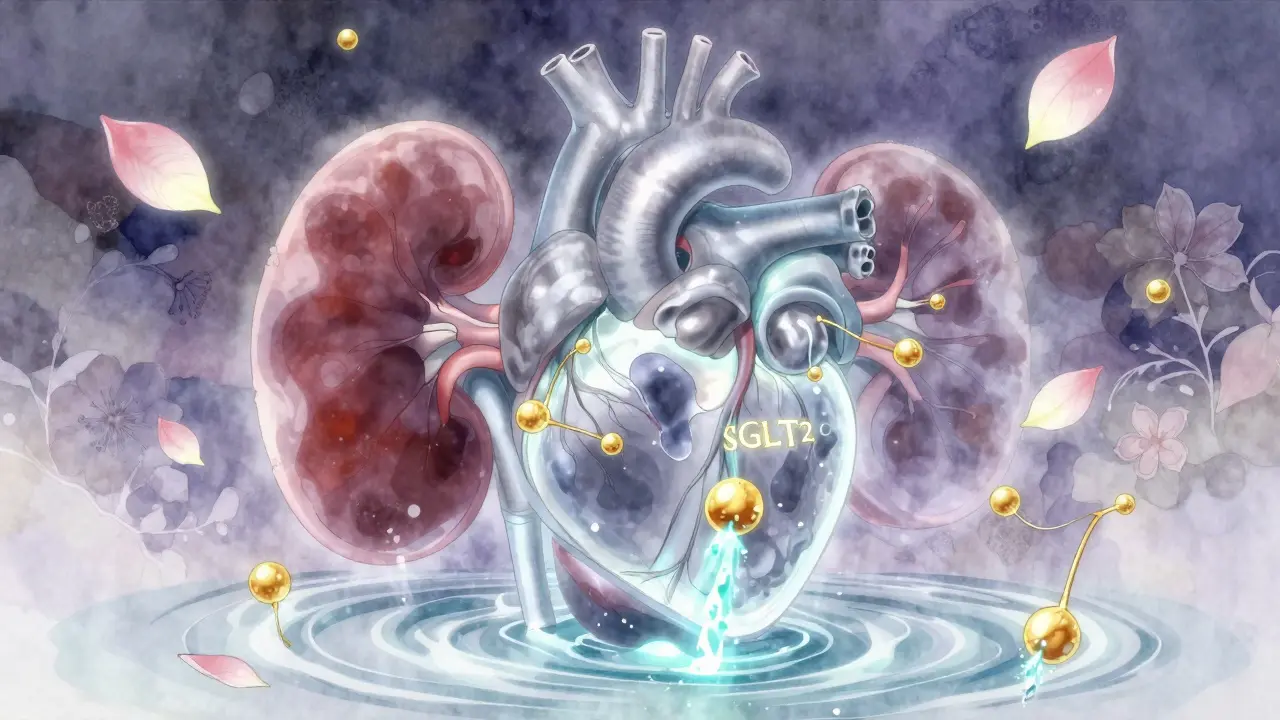

How SGLT2 Inhibitors Actually Work

SGLT2 inhibitors don’t work like insulin or metformin. Instead of pushing glucose into cells or making the body more sensitive to insulin, they let your kidneys flush out excess sugar through urine. The name comes from sodium-glucose cotransporter-2, a protein in your kidneys that normally reabsorbs glucose back into your bloodstream. These drugs block that process, so 40 to 100 grams of glucose-roughly 160 to 400 calories-get dumped out every day. That’s why people on these medications often lose 2 to 3 kilograms (4 to 7 pounds) without trying.

The first one approved was canagliflozin (Invokana) in 2013. Since then, dapagliflozin (Farxiga), empagliflozin (Jardiance), and ertugliflozin (Steglatro) have joined the list. All work the same way, but their dosing, how they’re cleared from the body, and their side effect profiles vary slightly. For example, empagliflozin is mostly removed by the liver, while dapagliflozin is cleared by the kidneys-so if your kidney function drops, your doctor may need to adjust your dose or stop it.

Why Doctors Now Prescribe Them First

Before 2015, SGLT2 inhibitors were prescribed only after metformin and other drugs failed. That changed after five major clinical trials involving more than 60,000 patients showed something unexpected: these drugs didn’t just lower A1c-they saved lives.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial found that empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 38% in people with type 2 diabetes and heart disease. The CANVAS Program showed canagliflozin lowered the risk of heart attack, stroke, or death by 14%. The DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial found dapagliflozin cut hospitalizations for heart failure by 17%. These weren’t small wins-they were game-changers.

What made these results even more surprising was that the benefits showed up even in patients whose blood sugar didn’t improve dramatically. That pointed to something deeper: these drugs were protecting the heart and blood vessels directly. Today, the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology both recommend SGLT2 inhibitors as first-line therapy for patients with diabetes who also have heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or a history of heart attack.

The Kidney Protection That Changed Everything

Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure in the U.S. SGLT2 inhibitors changed that trajectory. The CREDENCE trial, which focused on patients with diabetic kidney disease, showed canagliflozin reduced the risk of kidney failure, doubling of creatinine, or death from kidney disease by 30%. The DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY trials later confirmed that dapagliflozin and empagliflozin work the same way-even in people without diabetes.

By 2023, the FDA approved dapagliflozin for chronic kidney disease regardless of diabetes status. That’s huge. It means these drugs aren’t just for diabetics anymore-they’re becoming tools for preventing kidney decline in a broader group of high-risk patients. The mechanism? They reduce pressure inside the kidney’s filtering units, decrease inflammation, and slow scarring. These aren’t just sugar-lowering drugs anymore. They’re organ-protecting ones.

Heart Failure? These Drugs Help Even Without Diabetes

One of the most surprising discoveries was that SGLT2 inhibitors help heart failure patients-even those without diabetes. The DAPA-HF trial found dapagliflozin reduced hospitalizations and death from heart failure by 26% in people with reduced heart pumping ability. The EMPEROR-Preserved trial showed the same benefit in people with preserved heart function, which is harder to treat.

Doctors now use these drugs in heart failure patients regardless of whether they have diabetes. The number needed to treat to prevent one hospitalization or death over 16 months is just 21. That’s better than most heart failure medications. For someone with heart failure and type 2 diabetes, this isn’t a side benefit-it’s the main reason they’re on the drug.

The Real Risks: What No One Tells You

Benefits are impressive, but the risks are real-and often underdiscussed.

Genital yeast infections are the most common side effect. Up to 11% of women and 5% of men on these drugs develop them. That’s 3 to 5 times higher than on placebo. It’s not dangerous, but it’s annoying. Recurrent infections are why many people stop taking them.

Urinary tract infections are also more common, though less frequent than yeast infections. Most are mild, but if you get frequent UTIs, this might not be the best choice.

Dehydration and low blood pressure can happen, especially in older adults or those on diuretics. You might feel dizzy when standing up. That’s why doctors check your blood pressure and kidney function before starting and after a few weeks.

The scariest-but rare-risk is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Unlike typical DKA, which happens with very high blood sugar, this is euglycemic DKA: your blood sugar might be normal or only slightly high, but your body is burning fat for fuel and producing toxic ketones. It’s hard to spot because you don’t feel “sick” in the usual way. Symptoms: nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, fatigue, trouble breathing. The risk is low-0.1% to 0.3%-but it’s serious. You’re at higher risk if you’re sick, fasting, or having surgery. Your doctor should tell you to stop the drug temporarily during illness.

There’s also a small increased risk of Fournier’s gangrene, a rare but life-threatening infection of the genitals and perineum. The FDA added a black box warning for this in 2018. It affects about 2 in 100,000 users. If you notice sudden, severe pain, swelling, or redness in your genital area, go to the ER.

Canagliflozin carries a slightly higher risk of lower limb amputations, mostly toes and feet. The FDA requires a warning on this drug specifically. It’s rare-about 1 in 100 patients over 5 years-but if you have foot ulcers, poor circulation, or neuropathy, your doctor may avoid it.

Who Should Avoid These Drugs?

Not everyone is a candidate. You shouldn’t take an SGLT2 inhibitor if:

- You have type 1 diabetes (risk of DKA is too high)

- Your eGFR (kidney function) is below 30 mL/min/1.73m²

- You’re on dialysis

- You’ve had a previous episode of euglycemic DKA on this class of drugs

- You have severe allergies to any ingredient in the drug

If your kidney function is between 30 and 45, your doctor may reduce your dose or avoid it altogether. If it drops below 45 while you’re on the drug, they’ll likely stop it.

Cost and Access: The Hidden Barrier

These drugs are expensive. Without insurance, a 30-day supply costs between $600 and $650. That’s more than most diabetes pills. But most patients with insurance pay $10 to $25 a month thanks to manufacturer coupons and patient assistance programs. Still, if you’re uninsured or underinsured, cost can be a dealbreaker.

There are no generic versions yet. Patents don’t expire until 2027-2029. That means prices won’t drop soon. Some pharmacies offer discount programs, and manufacturers have free drug programs for low-income patients. Ask your pharmacist or doctor’s office-they can help you apply.

Real People, Real Experiences

One man, 58, with type 2 diabetes and heart failure, switched to Jardiance and saw his ejection fraction improve from 28% to 42% in 18 months. He hasn’t been hospitalized since.

A woman, 62, lost 12 pounds and got her A1c down to 6.5 on Farxiga-but she had three yeast infections in six months. She stopped it. "I felt great until I didn’t," she said.

Another user on Reddit lost 15 pounds in three months and said, "I didn’t change my diet. I just took the pill and it happened."

But cost and side effects are common reasons people quit. A 2023 study found 24% of patients stopped because of genital infections, 33% because of cost, and 18% because of dizziness or dehydration.

What to Do If You’re Considering SGLT2 Inhibitors

If your doctor suggests one, ask:

- Do I have heart failure, kidney disease, or a history of heart attack?

- What’s my current eGFR? Is it above 45?

- Have I had frequent yeast infections or UTIs?

- Am I on other drugs that lower blood pressure or cause dehydration?

- Can I afford this? Do you have a savings card or patient program?

If you’re already on one:

- Drink plenty of water, especially in hot weather or when you’re sick.

- Don’t skip meals or fast unless your doctor says it’s safe.

- Stop the drug if you’re hospitalized, having surgery, or very sick.

- Call your doctor if you have nausea, vomiting, or unusual fatigue-even if your blood sugar looks fine.

The Bottom Line

SGLT2 inhibitors aren’t magic pills. They’re powerful tools with clear benefits for people with diabetes who also have heart or kidney problems. For them, the upside far outweighs the risks. But for someone with just high blood sugar and no other complications, the benefit is smaller-and the cost and side effects may not be worth it.

They’ve reshaped diabetes care. But they’re not for everyone. The key is matching the drug to the person-not just the diagnosis.

Do SGLT2 inhibitors cause low blood sugar?

No, not on their own. Unlike insulin or sulfonylureas, SGLT2 inhibitors don’t increase insulin levels, so they rarely cause hypoglycemia. But if you take them with insulin, metformin, or other glucose-lowering drugs, your risk goes up. Always check with your doctor before combining medications.

Can I drink alcohol while taking SGLT2 inhibitors?

Moderate alcohol is usually okay, but it increases your risk of dehydration and ketoacidosis. Avoid heavy drinking, especially if you’re sick, fasting, or have kidney issues. Alcohol can also mask symptoms of low blood sugar, which is dangerous if you’re on other diabetes meds.

Are there any food restrictions with SGLT2 inhibitors?

No strict diet is required. But because these drugs make you lose sugar through urine, eating a very high-carb diet can cause more frequent urination and dehydration. A balanced diet helps manage side effects and improves results. Limiting sugar doesn’t make the drug work better-it just helps your overall health.

How long does it take to see results?

Blood sugar drops within the first week. Weight loss usually starts in 2-4 weeks. Blood pressure improvements show up in 3-6 weeks. But the big benefits-like fewer heart hospitalizations or slower kidney decline-take months or years to become visible. This isn’t a quick fix; it’s a long-term protection strategy.

Can I stop taking SGLT2 inhibitors if I feel fine?

Don’t stop without talking to your doctor. Even if you feel great, the drug is working to protect your heart and kidneys. Stopping suddenly can remove that protection. If side effects are a problem, your doctor can switch you to another medication-not just quit.

Is there a difference between the four SGLT2 inhibitors?

They’re very similar in how they work and their overall benefits. Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have the strongest evidence for heart failure. Canagliflozin has the most data on kidney protection and carries the amputation warning. Ertugliflozin has less proven benefit for heart failure. Your doctor will choose based on your kidney function, other conditions, and cost.

For most people with type 2 diabetes and heart or kidney disease, SGLT2 inhibitors offer protection no other pill can match. But they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution. The decision needs to be personal, informed, and ongoing.

Kipper Pickens

January 24, 2026 AT 15:18SGLT2 inhibitors are essentially renal glucose diuretics with pleiotropic cardiorenal effects-mechanistically fascinating because they decouple glycemic control from cardiovascular protection. The EMPA-REG and DAPA-CKD trials fundamentally rewrote the paradigm: we're no longer just managing hyperglycemia, we're modulating intraglomerular pressure, reducing tubuloglomerular feedback, and dampening inflammatory cascades via SGLT2 blockade. It’s not just a drug-it’s a disease-modifying intervention.

Aurelie L.

January 25, 2026 AT 07:54I got three yeast infections in six months. Stopped. Worth it? No.

Joanna Domżalska

January 27, 2026 AT 07:19So we’re just swapping one problem for another? You lose weight, sure, but now you’re peeing sugar and getting infections. Maybe the real problem is we’re treating symptoms instead of causes. Like, why not fix the diet? Or sleep? Or stress? Nah, let’s just flush it out.

Faisal Mohamed

January 28, 2026 AT 04:43These drugs are like nature’s cheat code 🤫✨ But the DKA risk? Yeah, that’s the ghost in the machine. I’ve seen patients go from ‘feeling fine’ to ICU in 36 hours. Don’t ignore nausea. Don’t fast. Don’t be a hero. 🚨

rasna saha

January 28, 2026 AT 10:14I’m so glad this was written clearly. My mom’s on Farxiga and was terrified of side effects. This helped her feel less alone. You’re not just a number on a chart-you’re a person with a life. Keep sharing stuff like this.

Skye Kooyman

January 29, 2026 AT 15:16Lost 15 lbs in 3 months didn’t change a thing. Still got the infections. Still paying $50 a month. Still wondering if it’s worth it

James Nicoll

January 31, 2026 AT 07:11So we’ve got a class of drugs that makes you pee out calories, protects your heart, and saves kidneys… but you can’t take it if you’re poor, or if you have a vagina, or if you breathe too hard. Sounds like capitalism with a stethoscope.

Uche Okoro

February 2, 2026 AT 00:09It is imperative to underscore that euglycemic DKA, while statistically rare, represents a critical clinical entity that demands heightened vigilance, particularly in the context of intercurrent illness or perioperative states. The pathophysiology involves a relative insulin deficiency coupled with elevated glucagon and catecholamine levels, leading to unchecked ketogenesis despite normoglycemia. Early recognition is paramount.

Ashley Porter

February 3, 2026 AT 20:09Empagliflozin’s effect on HFpEF in EMPEROR-Preserved was a game-changer. We used to think preserved EF meant ‘no treatment needed.’ Now we know it’s just a different kind of failure-and this drug hits it. Not magic, but science that works.

Peter Sharplin

February 4, 2026 AT 05:40For anyone considering this: get your eGFR checked before starting. If it’s below 45, ask why they’re still pushing it. And if you’re on diuretics or blood pressure meds, watch for dizziness. Hydrate like your kidneys depend on it-because they do. I’ve seen too many people get hospitalized for dehydration because they didn’t know the risk.

shivam utkresth

February 6, 2026 AT 04:02Man, I love how these drugs turned diabetes from a sugar problem into a whole-body story. It’s like we stopped seeing the pancreas as the villain and started seeing the heart and kidneys as the real victims. That shift? Huge. Also, I lost 10 lbs on Jardiance and didn’t even try. My jeans are happier than I am.

John Wippler

February 7, 2026 AT 05:12For the person who said ‘just fix your diet’-try working two jobs, raising kids, and eating what’s cheap and fast. Then come talk to me about ‘causes.’ This drug gave me back my energy, my walks, my life. I don’t care if it’s ‘band-aid medicine.’ It’s the band-aid that let me heal.