FAERS vs. Sentinel: Safety Detection Simulator

See how the FDA Sentinel Initiative improves drug safety detection compared to traditional reporting systems like FAERS.

Input Parameters

How This Works

FDA Sentinel uses real-world data from insurance claims and EHRs across millions of patients. It can calculate actual rates of adverse events because it has denominator data (how many patients took the drug).

Traditional FAERS only receives voluntary reports, which represent 1-10% of actual events. Without denominator data, it can't calculate rates accurately.

Comparison Results

FAERS System

Estimated adverse events detected: 0

Actual events (not detected): 0

Typically detects only 1-10% of actual events

FDA Sentinel Initiative

Estimated adverse events detected: 0

Actual events detected: 0

Detects actual rates with denominator data

Based on article data: Sentinel can detect safety signals in 4-8 weeks vs. months to years for traditional systems.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration doesn’t wait for people to get sick before acting. In fact, it doesn’t even wait for reports to come in. Thanks to the FDA Sentinel Initiative, the agency now actively watches what’s happening to millions of patients after they take a new drug - using real-world data, not just paperwork.

Before Sentinel, the FDA relied mostly on voluntary reports from doctors and patients through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). That system gets about 2 million reports a year. Sounds like a lot, right? But here’s the catch: experts estimate only 1% to 10% of serious side effects are ever reported. And even when they are, there’s no way to know how many people were taking the drug in the first place. Was the side effect rare? Or was it just underreported? Sentinel fixes that.

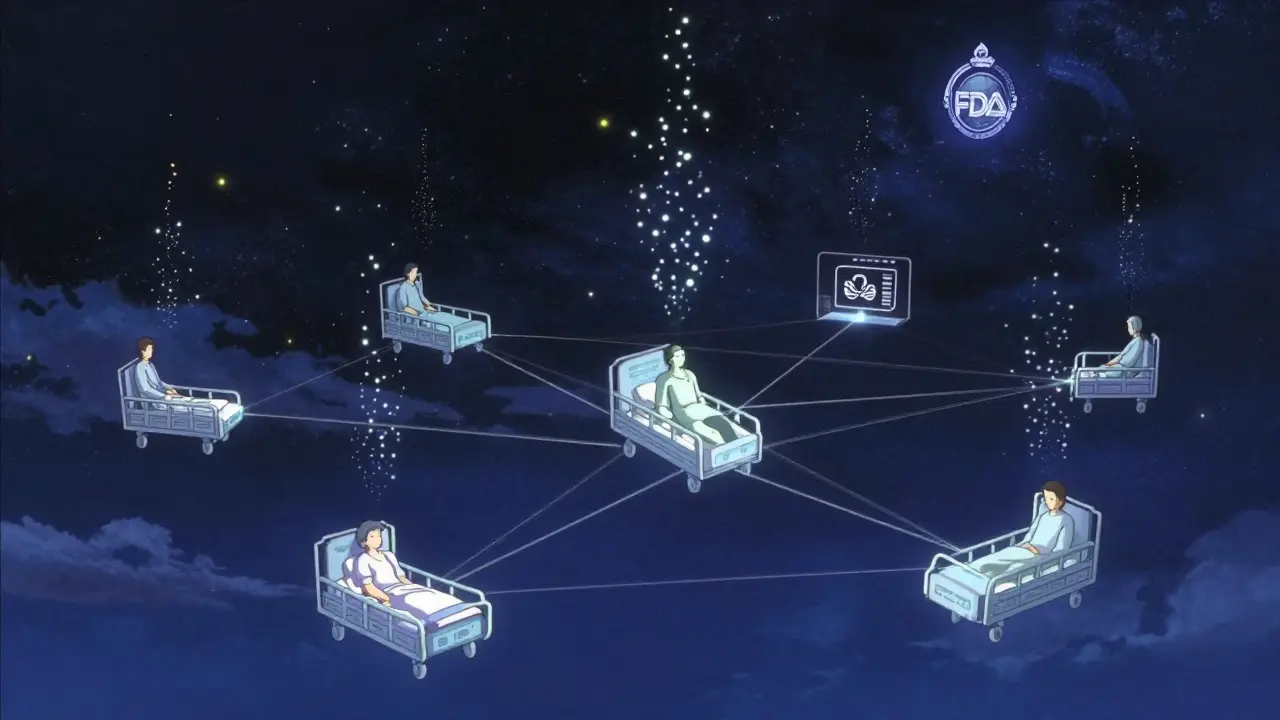

Launched in 2008 under the FDA Amendments Act, Sentinel started as a pilot called Mini-Sentinel. It tested a radical idea: what if the FDA didn’t collect data from hospitals and insurers? What if it just asked them to run the same analysis on their own systems? That’s the core of Sentinel. It’s not a database. It’s a network. Data stays where it is - with Kaiser Permanente, Humana, CVS Health, and dozens of other partners. The FDA sends a question - like, "Did people taking this new diabetes drug have more heart attacks than expected?" - and each partner runs the same query on their own records. Results come back anonymized and aggregated. No raw data leaves the building.

This distributed model isn’t just smart. It’s necessary. Privacy laws like HIPAA make it impossible to move patient records across systems. But Sentinel works around that. It uses standardized tools so every partner answers the same question the same way. That means results are reliable, even when data comes from different hospitals, insurers, or EHR systems. By 2016, the full Sentinel System was live. Today, it’s the largest multisite distributed database in the world dedicated to drug safety.

What kind of data does it use? Originally, it leaned on insurance claims - things like diagnosis codes, prescriptions filled, and hospital visits. But claims data is limited. It tells you someone went to the ER with chest pain, but not whether they had a prior heart condition, what their cholesterol was, or if they were on other meds. That’s why Sentinel started pulling in electronic health records (EHRs). These include doctor’s notes, lab results, vital signs, and even unstructured text like "Patient reports dizziness after starting new medication." The Sentinel Innovation Center is now using artificial intelligence to dig through those notes, turning messy clinical language into usable signals.

The system has already changed how drugs are monitored. In 2018, Sentinel flagged a possible link between a popular antiviral and a rare heart rhythm disorder. The FDA reviewed the data, confirmed the risk, and updated the drug’s label within months. In 2021, it helped evaluate whether a flu vaccine increased the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome in older adults - a question that would’ve taken years to answer with traditional studies. Sentinel did it in under six weeks.

It’s not perfect. EHRs are messy. One hospital codes "high blood pressure" as I10. Another uses 401. Some don’t record allergies at all. And not every patient is in the system - homeless people, undocumented immigrants, or those who only get care in emergency rooms might be invisible. But Sentinel doesn’t pretend to be complete. It’s designed to spot patterns, not every outlier. When a signal appears - say, a spike in kidney injuries among users of a new painkiller - the FDA can then run targeted studies to dig deeper.

The system also handles vaccines. The Postmarket Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring (PRISM) system, built inside Sentinel, tracks vaccine safety in real time. After the COVID-19 vaccines rolled out, PRISM helped confirm the extremely rare risk of myocarditis in young men - and also showed the benefit far outweighed the risk. That kind of speed and precision was impossible before Sentinel.

Who uses it? The FDA is the main driver, but it’s not alone. Pharmaceutical companies use it to monitor their own drugs. Academic researchers run studies through the Innovation Center. International regulators from Europe and Canada collaborate on joint analyses. Even the CDC and NIH have used Sentinel data for public health studies. It’s become a shared national resource - like a public highway for drug safety research.

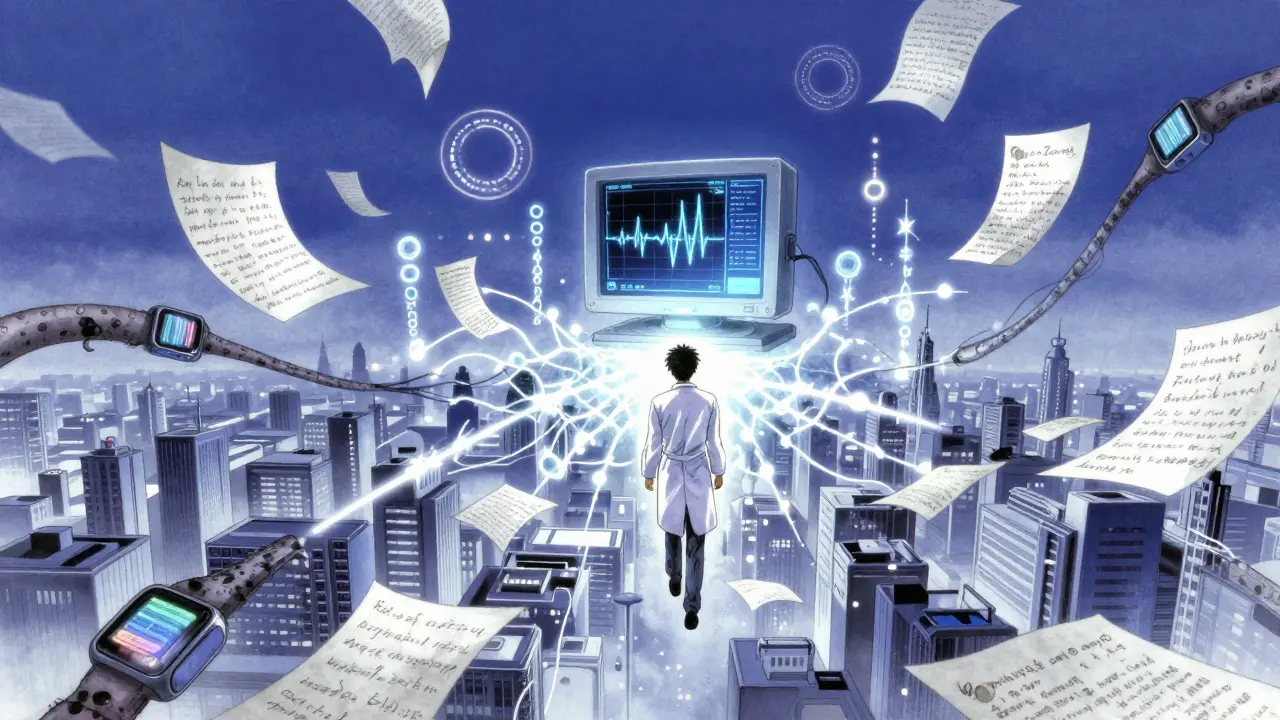

The future? Sentinel 3.0 is already underway. With $304 million in funding, the system is expanding its AI tools, refining how it handles unstructured data, and building better ways to prove cause-and-effect. Right now, it can say "this drug was linked to more heart attacks." But can it say "this drug caused heart attacks in patients with low kidney function who also took statins?" That’s the next level. The Innovation Center is training machine learning models to mimic randomized trials - something once thought impossible with observational data.

It’s not just about drugs anymore. Sentinel now monitors medical devices, biologics, and even dietary supplements. It’s becoming the backbone of a learning health system - one that gets smarter every time a patient takes a pill, gets a shot, or visits a doctor.

For regulators, it’s a game-changer. For patients, it’s peace of mind. And for the companies that make medicines, it’s a way to prove safety - not just promise it.

How Sentinel Compares to Traditional Drug Monitoring Systems

| Feature | FDA Sentinel Initiative | Traditional FAERS System |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Real-world data from insurance claims and EHRs (millions of patients) | Voluntary reports from doctors, patients, and manufacturers |

| Reporting Volume | Continuous, automated updates | ~2 million reports per year (estimated 1-10% of actual events) |

| Denominator Data | Yes - knows how many people used the drug | No - no way to calculate rates |

| Speed of Detection | Weeks to months | Months to years |

| Data Detail | Includes clinical notes, lab results, comorbidities | Basic symptoms, drug name, patient age |

| Privacy Model | Distributed - data never leaves partner systems | Centralized - reports sent to FDA database |

| Regulatory Impact | Directly informs label changes, safety alerts | Used for trend spotting, rarely drives action |

Why Sentinel Is a Global Model

Other countries have tried similar systems. The UK has the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Canada has the Canadian Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring System. But none match Sentinel’s scale or integration with regulatory decision-making. What makes Sentinel unique isn’t just the data - it’s the structure. It was built from the start to be a national infrastructure, not just a research project.

The three coordinating centers - the Sentinel Operations Center, the Innovation Center, and the Community Building and Outreach Center - make sure it stays responsive. The Operations Center handles day-to-day queries. The Innovation Center pushes the limits with AI and machine learning. The Community Center trains researchers and builds trust with data partners.

And it’s working. Since 2016, Sentinel has completed over 400 safety analyses. More than 60 of them led directly to FDA regulatory actions - label changes, new warnings, or even drug withdrawals.

Who Benefits From Sentinel?

- Patients - get safer medications because hidden risks are caught faster.

- Doctors - have better information to choose the right drug for the right patient.

- Pharmaceutical Companies - can proactively monitor their products and avoid costly recalls.

- Regulators - make decisions based on real-world evidence, not just theory.

- Researchers - access data that would otherwise take decades to collect.

What’s Next for Sentinel?

The next phase is about depth. Right now, Sentinel mostly sees what happens in hospitals and clinics. But what about patients who don’t go to the doctor? What about mental health side effects? Or long-term impacts over 10 years?

The Innovation Center is testing AI models that can read doctor’s notes like a human. If a patient writes, "I feel weird after taking this pill," and 5,000 others say the same thing, the system learns to flag it - even if no code was entered.

It’s also working with wearable tech. Imagine a patient with a smartwatch that tracks heart rate. If a new drug causes irregular pulses, and 10,000 wearables show the same pattern, Sentinel could detect it before a single hospital report is filed.

And it’s going global. The FDA now shares protocols with regulators in Europe and Japan. The goal? A worldwide network where safety signals can be detected across borders - not just in the U.S.

How is Sentinel different from the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)?

FAERS relies on voluntary reports from doctors and patients - it’s passive and incomplete. Sentinel uses real-world data from millions of patients across healthcare systems, giving it denominator data (how many people took the drug) and clinical details that FAERS lacks. Sentinel can detect patterns quickly; FAERS often takes years to spot trends.

Does Sentinel collect personal health information?

No. Data never leaves the partner organizations. Sentinel sends encrypted analytical queries to hospitals and insurers, and they run the analysis on their own secure systems. Only aggregated, anonymized results are sent back to the FDA. No names, Social Security numbers, or addresses are shared.

Can researchers outside the FDA use Sentinel?

Yes. The Sentinel Innovation Center runs demonstration projects that let academic researchers, industry scientists, and international regulators use the system to answer their own safety questions. Training and tools are provided to help them design queries and interpret results.

What kind of data does Sentinel use?

Sentinel uses insurance claims data (prescriptions, hospital visits, diagnoses) and electronic health records (lab results, vital signs, doctor’s notes). The system is now expanding to include data from wearable devices and patient-reported outcomes to get a fuller picture of drug effects.

How long does it take Sentinel to detect a drug safety issue?

It can take as little as 4 to 8 weeks to confirm a signal - compared to years for traditional studies. The system can analyze millions of records in near real-time, making it possible to catch rare side effects before they become widespread.